The opposition to the farm laws first emerged from the Punjab peasantry who carried out protest actions in the form of blocking of highways, railway tracks, shutting down toll plazas, corporate owned petrol pumps, malls, and silos along with demonstrations in front of local administration and elected representatives in July 2020 soon after the Union government passed the agri-ordinances in June, 2020.[1] More than 30 farmer organisations in Punjab came together and intensified the protests at state level. Jail bharo aandolan (voluntary court arrest), a bandh (general strike), rail roko (halting trains), and highway blockades were organised in the following months. Farmers in neighbouring states of Haryana and Rajasthan also observed protest calls during this period.

On November 7, 2020, a joint platform, Sanyukt Kisan Morcha (United Front of Farmers’, SKM) comprising around 500 farmer organisations representing tens of millions of farmers all over the country was constituted to lead the agitation against the farm laws. Once the acts were passed by Parliament in September 2020, the build-up of a spate of local protests in Punjab and Haryana led to an important development for the struggle, the call to “Dilli Chalo” (March on Delhi) given by the farmer organisations on November 26-27, 2020. Before this, The AIKSCC gave a call for countrywide protest actions on September 25. The farm leaders after a meeting in Delhi on October 27 gave a call of nationwide road blockades on November 5 to protest against the new laws. The AIKSCC gave a call for a ‘gramin bandh’ (rural strike) in solidarity with the trade union general strike on November 26, 2020 as the farmers marched towards Delhi under the call of Dilli Chalo.

Alarmed by the Dilli Chalo call and for an all-India general strike called by major trade unions on November 26, the Haryana police raided the homes and offices of farmer-organisers and trade unionists at several places across the State on the night of November 24. The police took around 30 leaders and activists into preventive custody ahead of the Delhi March. However, the all-India strike was a huge success, and saw the participation of hundreds of thousands of workers cutting across all sections. The farmers’ march was not allowed to enter Delhi resulting in hundreds of thousands of farmers setting their camps on the borders of the capital city.

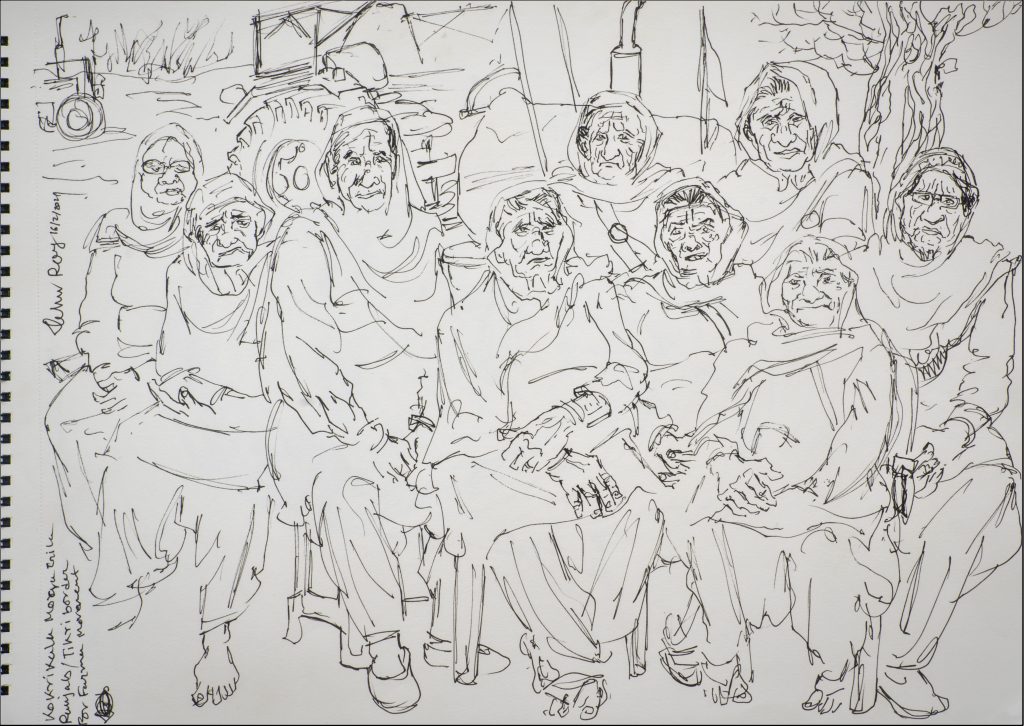

Unprecedented methods were used to keep protestors from marching towards Delhi. Farmers from Punjab, for example, who tried to enter the neighbouring state of Haryana enroute Delhi, faced heavy barricading, dug-up roads blocked by boulders, large concrete pipes, wires and huge piles of sand. At various points the police used tear gas and water cannon to disrupt the march. However, the lines of tractor-trolleys kept getting longer as more farmers joined the protestors. Tractors and earth movers were brought from nearby villages to repair dug-up roads and remove blockades until, after a point, it seemed impossible to stop the marchers. Free community kitchens (langar) and cooked food stalls mushroomed overnight along the national highways passing through Haryana, where rural volunteers served food and made other arrangements for farmers. It was clear that the plans to stop the farmers from reaching Delhi had proved counter-productive. On November 27, the marchers reached two entry points to the national capital, Singhu (on National Highway 44) and Tikri (on National Highway 9). They were stopped at these points, although they demanded access to Jantar Mantar, the place in Delhi designated for public protests. On November 28, when the Home Minister invited farmers’ leaders for talks, the police asked them to vacate the roads and shift to another place. The farmers refused to shift from the borders of the city.

After the protesting farmers sat at the borders, farmers from other parts of country, including Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttarakhand, and Uttar Pradesh joined their ranks. Police in these states tried to prevent them from marching towards Delhi, and arrested many. Within a few days new border protest sites sprung up. These were at Ghazipur (where farmers from Uttar Pradesh joined), Shahjahanpur Kheda (on National Highway 48), where farmers from Rajasthan joined, Palwal (on National Highway 2) where farmers from Haryana, Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh put up their tents, and Dhansa-Badli (close to Gurugram) where farmers from southern Haryana started a protest site. A convoy of thousands of farmers that started from Maharashtra’s Nashik reached the border of Delhi at Shahjahanpur on December 25. By the end of December (2020), farmers from other Indian States were involved.

Leaders of the movement worked to give the struggle a more all-India character; they made regular visits to different States to address farmers about the impact of the new farm laws and to mobilise support for the protests.[2]

While the agitation began with the demand to withdraw the farm-laws, there was both spatial and thematic growth during the course of the protest providing a new lease of life to farmers’ mobilisation on State-level and local issues across the country.